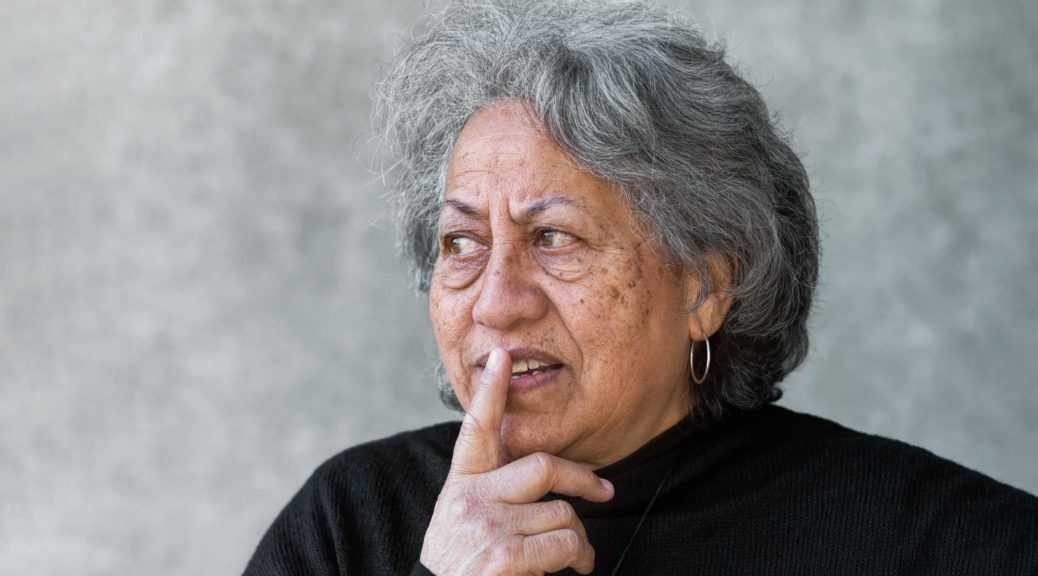

KURA TE WARU-REWIRI

Ngāti Kahu, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāti Rangi

Whiti o Rehua School of Art

Although best known as one of New Zealand’s most celebrated Māori woman artists, Kura Te Waru-Rewiri from the School of Art sees giving back to her community as her most important focus. ‘If I was to look at myself from the outside to what people would identify me by first, it would be my art,’ she said. ‘But for me, it’s all about my whakapapa [genealogy], and that I’m Māori. I was brought up in Waitangi, and I was born in a little settlement called Kaeo. My attachment to my marae was from birth, and I sit there now as the chairperson of the marae trustees. That’s the core of my being — the marae is central to what I do.’

Colonisation, she says, has had a major impact on Māori art, particularly for Northland iwi Ngāpuhi, who were the first to lose their customary art forms. Now, Te Waru-Rewiri is working with a group of other Ngāpuhi artists to bring artists together and regenerate Ngāpuhi art across the board, from the contemporary practice of carving, weaving and tā moko (traditional tattooing), to performing arts such as kapa haka. The group has recently gained funding from Creative New Zealand to help with these initiatives.

For Te Waru-Rewiri, it is of central importance that this work is artist-led. ‘We said from the very beginning that we need to feel that artists are leading this initiative,’ she said. ‘We have a vision and the vision is not to control, but to empower. Our strategy incorporates education for Ngāpuhi as well. We were inspired and motivated by the fact that there’s talent everywhere in our young people at home. How can we assist and bring attention to them in an area that’s relatively poor, rural and isolated? In education, we’re looking at how Māori artists can support Māori art programmes in schools, and one of us has set up a relationship with a couple of schools up north to start the ball rolling. We also have a group of Māori artists who are interested in helping.’

In terms of her own art practice, Te Waru- Rewiri has had a varied career. ‘My first works were to do with the way I see myself as a Māori woman,’ she said. ‘I did a thesis in my honours year at Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch on stone tool carving, and there’s something very spiritual about the use of stone tools in comparison to steel tools. I went from that to painting the carved figurative forms of the Ngāpuhi style of carving, which is a domed headand sinewy figure. I painted them, but people thought I’d carved them. I have used a variety of styles during my practice, but my relationship was always with the paint. I have an appreciation for pigment and paint powders. I played with paint so I could pull out as much as I could.’

The other important area for Te Waru-Rewiri is the maintenance of customary art forms and the narratives that come from these. This was put to the test when she was involved in designing and painting Te Puna o Te Mātauranga Marae at NorthTec in Whāngārei, which involved rethinking the traditional while paying due respect to it. ‘There were a few anxious moments between the institution and the hapū [subtribe] associated with the marae, as they did not want the whare to represent ancestors. And then I thought, it’s a licence to do it in another way. The light went on and I decided to use pattern and design from kōwhaiwhai, tukutuku [painted scroll patterns and ornamental latticework] and carvings. This meant all the anxiety flowed out of my body and freed me up to create this concept and work with weavers and carvers, as well as the painting. I had one person plus my son helping me with the paintings in the whare, and as the major contributing artist, I produced a lot of work, such as the tāhuhu, which is the big rib of the whare up in the ceiling, that was 18 metres long.’

Although she is hesitant about being placed in too strict a category as an artist, Te Waru-Rewiri does concede that, overall, most of her work has a political angle. ‘I guess in lots of ways, I’m a political artist. The core of my inspiration is the Treaty of Waitangi, and everything that has evolved from my work and concept development has been around the impact of colonisation. But in my involvement with my own iwi, it’s giving back time.’