New research shows that New Zealand Orthoptera don’t conform to the metabolic cold adaptation hypothesis.

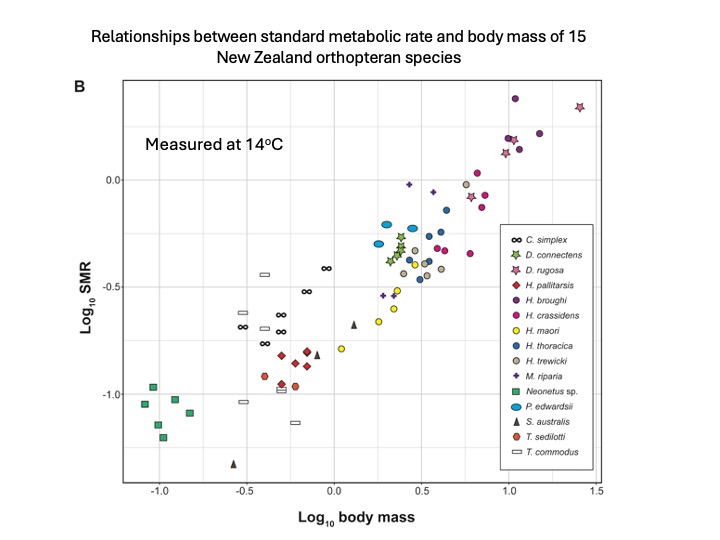

Metabolic rate varies with body size but when size is considered in concert with other factors many cold-adapted organisms show faster metabolic rate than their warm-adapted cousins at the same test temperature. But this is not what we see in Aotearoa NZ.

In NZ most of our native wētā and cricket diversity is nocturnal and many species are tolerant of cool temperatures or even thrive in cold places. However, their metabolic rates do not support the theory that to cope with the challenges of the cold, alpine insects run their engines faster.

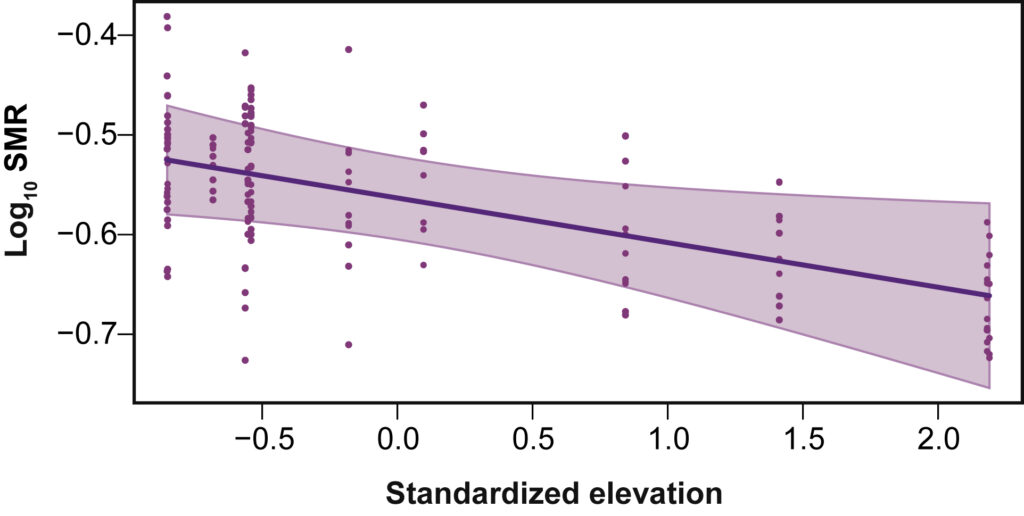

The metabolic cold adaptation hypothesis predicts that ectotherms from colder climates (high latitudes or elevations) have steeper thermal performance curves and elevated metabolic rates at the same test temperature compared to those from warmer environments . We found that New Zealand insects from higher elevations and latitudes had lower standard metabolic rates than expected.

As our planet rapidly warms we need to consider the thermal sensitivity of our wildlife. This is the capacity of an individual animal to change its metabolic rate as a response to increases in temperature. Two localized, declining wētā species (Deinacrida rugosa and Motuweta riparia) have high thermal sensitivity of metabolic rate. Climate change will elevate the average temperature wēta experience resulting in increased metabolic rates in these thermally sensitive species, thus requiring greater energy expenditure. This will be an added challenge to species already facing threats from habitat loss and novel predators.