New Zealand stick insects have invaded the United Kingdom, but in the process they have lost the ability to reproduce sexually. This is odd because the vast majority (more than 99%) of multicellular creatures (primarily eukaryotes) engage in sex during reproduction.

Sex involves two individuals with different properties. Typically one sex (the male) produces abundant small and often motile gametes that carry genetic information to the larger egg produced by the other (female). Through this process, genetic information is passed from two parents to their offspring and results in shuffling of genetic variation. The results are readily evident in the variation seen among offspring that is prominent in human families.

Stick insects are (mostly) no exception even though scientist can show that reproduction without two sexes can have a numerical advantage over sexual reproduction. Simply, females that make only self-fertile daughters leave more of their genetics to future generations. Theoretically it seems that clonal reproduction is advantageous, as long as the environment does not vary too much; producing offspring that are not the same as the parent could make some of them less successful. It is telling then, that despite the numerical advantage of clonal reproduction, that vast majority of large organisms do use sexual reproduction. Natural selection has made its choice.

One group of New Zealand stick insects includes individuals that differ in colour, size, and shape. In particular the number and size of spines they have varies among individuals. This group (genus Acanthoxyla) includes several described species, although in this case defining species is difficult. All are female, which means all come from self-fertile eggs produced by one parent (the mother). Hatchlings grow up to look like their mums, so are effectively clones.

One group of New Zealand stick insects includes individuals that differ in colour, size, and shape. In particular the number and size of spines they have varies among individuals. This group (genus Acanthoxyla) includes several described species, although in this case defining species is difficult. All are female, which means all come from self-fertile eggs produced by one parent (the mother). Hatchlings grow up to look like their mums, so are effectively clones.

Among the many individuals of common and widespread Acanthoxyla (literally: prickly stick) observed in New Zealand, no male has been encountered. Yet. But recently a male belonging to this genus turned up in England.

Among the many individuals of common and widespread Acanthoxyla (literally: prickly stick) observed in New Zealand, no male has been encountered. Yet. But recently a male belonging to this genus turned up in England.

Rare males like this emerge among all-female stick insect populations, probably as a result of a random mutation deleting one of the XX sex chromosomes that denotes a female stick insect. XO individuals are male in appearance, but are usually not reproductive.

Research on the New Zealand genus Clitarchus has been revealing about the switching between sexual and asexual (all female) reproduction. As reported in Nature a population of Clitarchus hookeri accidentally introduced to the UK about 100 years ago has lost not only its homeland but also its sex life.

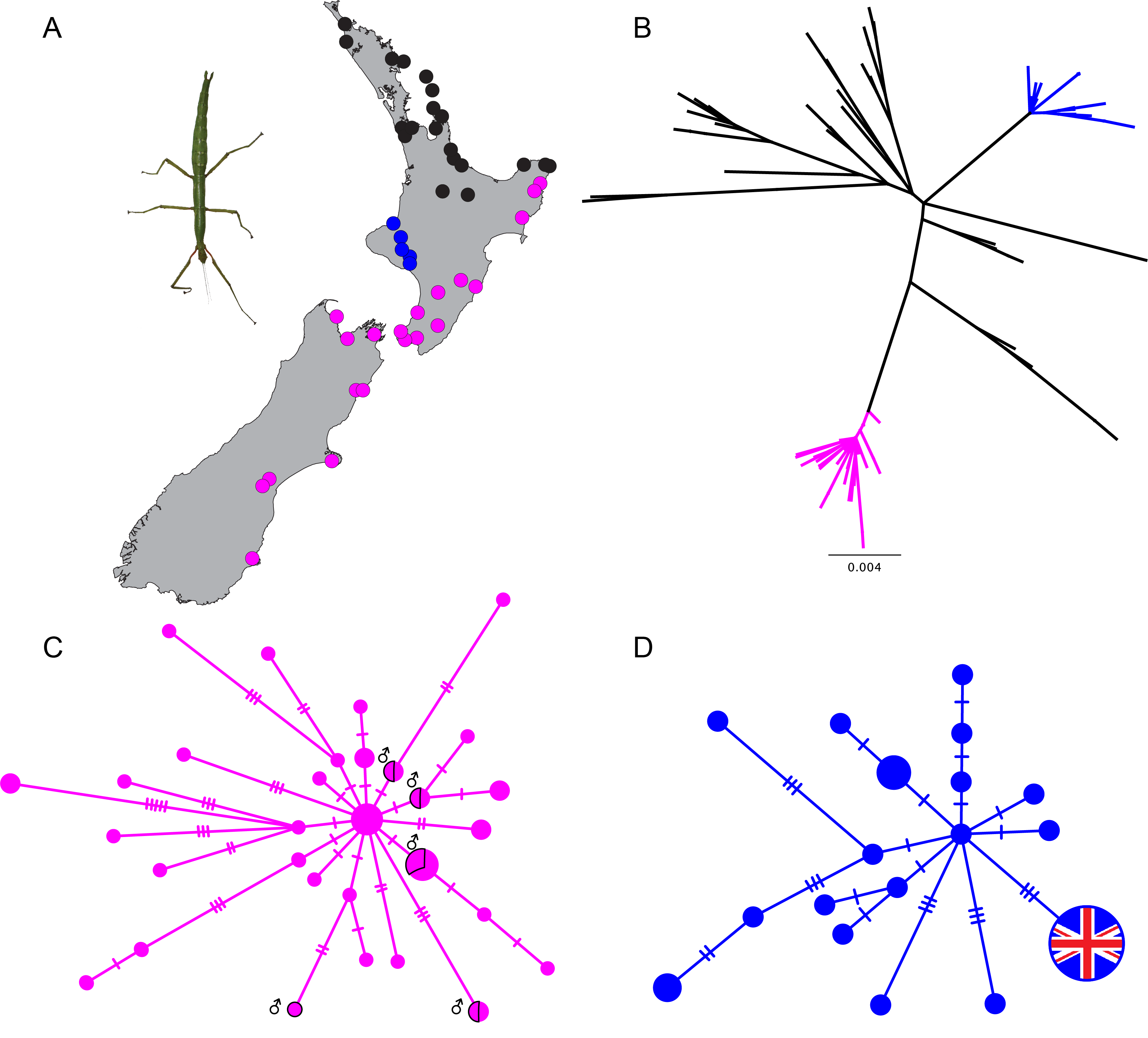

Analysis of genetic variation shows that the origin in New Zealand of the UK stick immigrants was most likely in Taranaki, North Island. This agrees with historical records indicating that native plants collected in this area were shipped to England and then the nearby Isles of Scilly. In particular the Abbey Gardens on Tresco are now home to a range of New Zealand plants, and it is likely that stick insect eggs in the soil around plant specimens were accidentally transported around the world. Hatchlings that grew into adult stick insects able to produce abundant self-fertile females were likely at an advantage. The potential of this species to switch to asexual reproduction has also resulted in a pattern of geographic parthenogenesis in New Zealand.

Genetic variation (mtDNA COI) in Clitarchus hookeri across New Zealand (A, B), highlighting the mainly parthenogenetic lineage in NZ (C), and the lineage associated with the one variant found in the UK population (D).

Closer examination of two New Zealand populations of the same species add to our understanding of the drivers and mechanisms of reproduction strategy switching. The UK population lost sexual reproduction and evolved a barrier to fertilisation, which has been demonstrated by providing captive female stick insects from UK with NZ males. Meanwhile two NZ populations recently gained sexuality and genotypic data indicate this happened via two different pathways.

Original Science:

Morgan-Richards M, Langton-Myers S, Trewick S. 2019. Loss and gain of sexual reproduction in the same stick insect. Molecular Ecology

Trewick SA, Morgan-Richards M. 2018. Missing New Zealand stickman found in UK. Antenna 42: 10–13.

Comment:

Nature

Media:

Guardian

Telegraph

STUFF/Dominion Post

BBC radio