Scientists in the Wildlife & Ecology group (School of Food Technology and Natural Sciences) Massey University have identified genes that might explain resistance to toxins in brushtail possums. The science by Dr David Carmelet-Rescan, Professor Mary Morgan-Richards and Professor Steve Trewick of the research group Te Taha Tawhiti is reported in The Journal of Comparative Physiology B

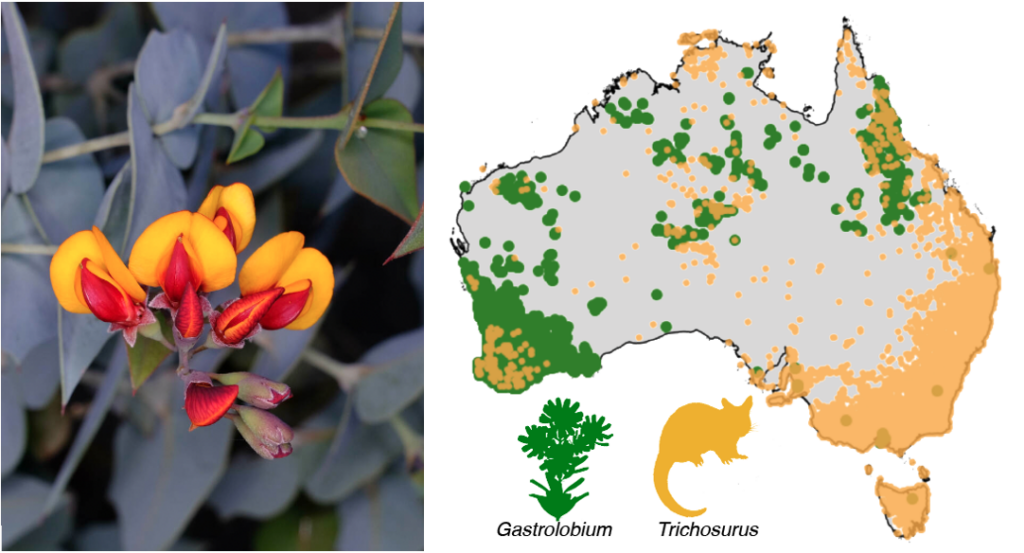

Multiple genes have been identified that might explain why some possums can tolerate high doses of plant toxins. The scientists compared functioning genes from wild brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) that came from east and west Australia, known to have contrasting tolerance to 1080. The lethal does of 1080 for brushtail possums in WA is about 150 times higher than for eastern possums.

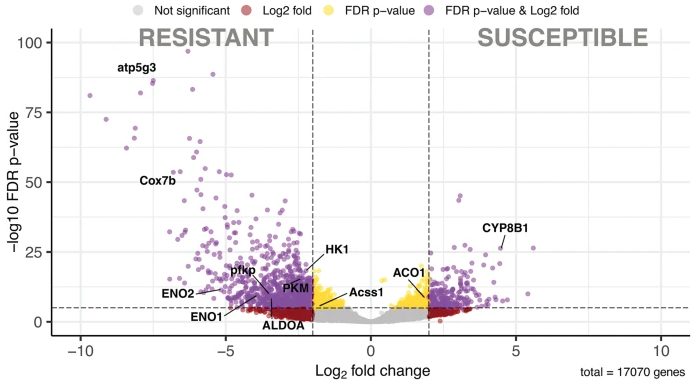

By comparing genomic data from possums in these different populations it was possible to identify genes that are expressed differently. The research focussed on gene expression in the liver which is recognised as a centre of toxin breakdown in mammals. Some of the differences in expression that were found are associated with differences in the response of the possums to what they eat.

1080 is a mammal toxin that is naturally produced by many plant species to protect their leaves from leaf-eating animals. It is more abundant in plants in Western Australia than east Australia, where the possums introduced to New Zealand came from.

Animal cells use a series of chemical reactions known as the citric acid cycle to release energy from nutrients including carbohydrate, fat, protein and even alcohol. That means this system is not only the powerhouse of animal life but it contributes to the break-down of a wide range of compounds some of which are toxins. 1080 produced by plants disrupts this critical mechanism. Adaptations by West Australian possums involve genes associated with the citric acid cycle linked to toxin tolerance.

The research indicates a number of different genes linked to the citric acid cycle are involved in the greater tolerance to 1080 displayed by West Australian possums. Although no WA possums were brought to New Zealand, the NZ invasive population is genetically diverse because of the number and range of possums originally introduced from southeast Australia and Tasmania. The resulting genetic mixture means there is lots of variation on which natural selection can act.

Next steps in this research are to measure expression of implicated genes in New Zealand possum populations.

Possums are omnivores that eat native plant and animals that reduce resilience of our ecosystem. They are also the primary carrier of the infectious disease Bovine tuberculosis in New Zealand so a major concern for agriculture and the economy. The main method of control across Aotearoa New Zealand is aerial application of Compound 1080- monofluoroacetate.

Although a source of controversy the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment report in 2011 came out in support of continued use of 1080 as the best solution to a major pest problem. Bearing in mind the proposal to eradicate possums and several other introduced mammals from New Zealand by 2050, 1080 remains a priority tool. However, there is the possibility that possums in New Zealand will evolve increasing resistance to 1080 as a result of repeated exposure around the country. Natural selection will favour any individuals with genetics that helps their survival, so it is probable that resistance to 1080 will emerge. Evolutionary responses to human actions are documented in many different circumstances including insecticide resistance in the Lucilia flies that cause fly strike in sheep, and bacterial resistance to most antibiotic medicines.

Project leader: Professor Steve Trewick

PhD researcher: David Carmelet-Rescan, supported by a scholarship from OSPRI. Dr Carmelet-Rescan is currently research fellow at Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Italy.