In the pursuit of food systems change, it is critical to not view global crises through a monocular lens of product development opportunities.

When developing future foods, they should be approached from multiple lenses and with a myriad of tools.

Māori future foods have a dual opportunity and challenge of incorporating cultural, social, and environmental imperatives in food product development. Branding is one tool for Māori enterprise to communicate value-led food production.

My research focuses on Māori future foods from multiple angles, with a view of how they are produced, and eaten. I have also focused on abstract aspects of consumption, including how consumers perceived Māori branding.

A sense of global culture

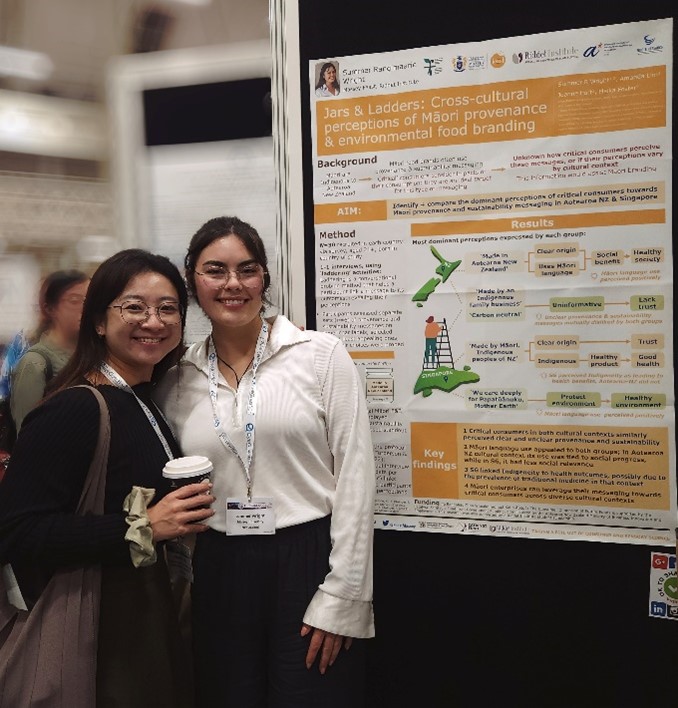

Together with colleagues on Te Rangahau Taha Wheako mō ngā Kai o Āpōpō, the Consumer Dimensions of Future Foods project, I presented at the 11th European Conference on Sensory and Consumer Research in Dublin, Ireland, September 2024. Largely food focused, the conference brought together nearly 700 delegates.

Riddet Institute generously supported me to attend with a poster, which aligned to the conference’s central theme of ‘A Sense of Global Culture’. The poster presented research that explored consumer perception of Māori food branding, which makes up my wider thesis on Māori future foods.

The research highlighted how different components of Māori branding, such as the use of te reo (Māori language) and cultural expressions resonate across local and global contexts.

Global culture not without challenges

Māori-made future foods can incorporate multiple lenses in food product development.

When thinking about a food production pipeline, protection of culture may not come to the front of your mind. However, for Māori food enterprise, protection of mātauranga (Māori knowledge and knowledge system) is often a KPI. When branding food, Māori enterprise are careful in the use of cultural elements because they are collectively held and treasured, and associated with particular people and places.

A globalised food culture can be advantageous for Māori, as it enables export of value-led food offerings and enhances local Māori economies. At the same time, a global culture can pose threats to Indigenous knowledge protection. It can be incredibly difficult to protect collective knowledge in legal frameworks that are founded on notions of private property, and yet more difficult once that knowledge becomes global.

My poster showed that a statement like ‘Made in Aotearoa New Zealand’ lends legitimacy to Māori-made food, because it seems more authentic. However, it is difficult to protect such a statement from misuse. Māori language is already being commodified by multinational corporations to facetiously identify their global brand as a local Aotearoa one, by using te reo:

Left: Dutch multinational product, Right: Māori-made product

Understanding how local and global consumers perceive elements of Māori branding can highlight appealing elements that are not easily misappropriated.

A statement like ‘Made by Māori’ is difficult to lie about, and my research showed that Singaporeans value this term for its transparency and positive physical and environmental health connotations.

Moreover, a Māori value-led food chain is not replicable. Applying cultural, social, and environmental imperatives to food production achieves benefits that reach beyond food product development.

In my research, Aotearoa NZ participants positively judged the statement ‘Made at the marae’ because they acknowledged the wide-reaching benefits of marae-based food production, which included Māori wellbeing and a healthy community.

Riddet and Massey Feast presence

Fellow Riddet student Yunfan (Nancy) Mo and I enjoyed our time in Dublin. We got a taste of Ireland at the Guinness Storehouse.

Jo Hort, Fonterra Riddet Chair in Consumer & Sensory Science was invited to give the opening Conference Keynote, and the Feast team were there in force.

Māori future foods: more than koru imagery?

The funniest joke I heard at the conference was made by previous A*STAR Future Foods colleague Ciaran Forde, who delivered a keynote about future foods. He remarked that the most common imagery associated with future foods is a conventionally beautiful woman laughing at a salad; you already know this picture!

So, when thinking about Māori future foods, what comes to mind? A Māori smiling at a kumara, or something more?

Considering the first statements made in this article, Māori future food development can incorporate cultural, social, environmental imperatives, alongside product development ones, to enables multiple positive outcomes. Branding is one tool within a Māori food value chain for the communication of value-led food production.

Funding: Rangahau Taha Wheako mō ngā Kai o Āpōpō, The Consumer Dimension of Future Foods is supported by the Catalyst: Strategic Fund from Government Funding, administered by the Aotearoa New Zealand Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment. This research was also supported by a Riddet Institute student scholarship.