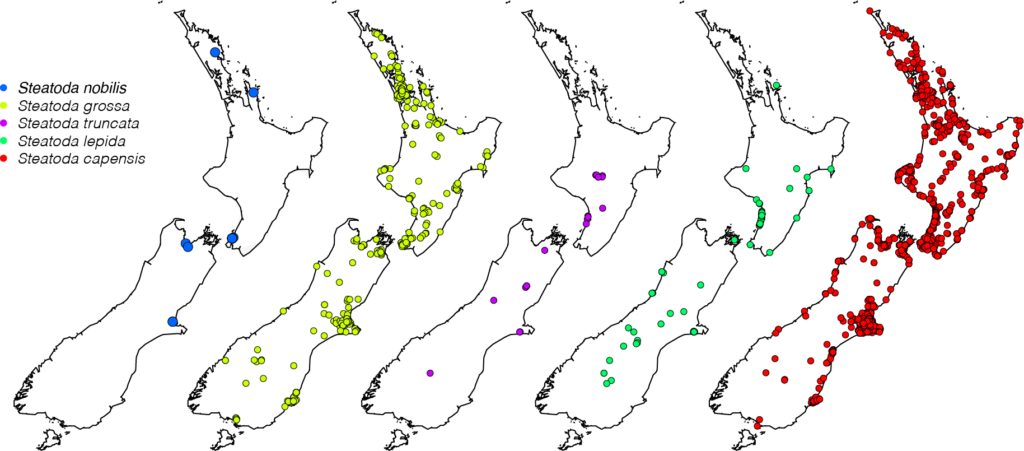

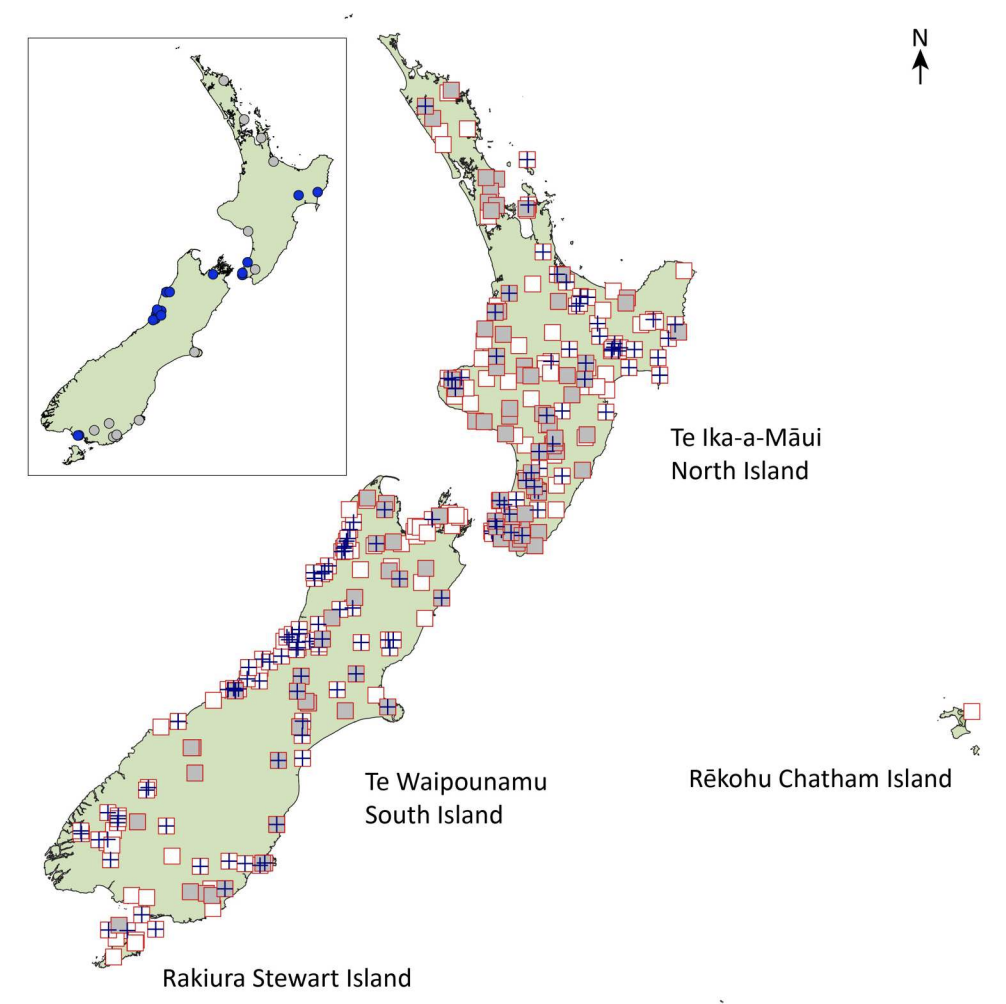

Ground wētā are those species of flightless crickets endemic to Aotearoa-New Zealand that conceal themselves in daytime in soil burrows. Recently we showed that this lifestyle has been adopted by two separate evolutionary lineages in NZ; Hemiandrus and Anderus.

Though species in these two genera are all considered to be ground wētā, each group is more closely related to separate king crickets in Australia that to each other. The name Hemiandrus was established in 1938 but Anderus was formally recognised more recently in 2024.

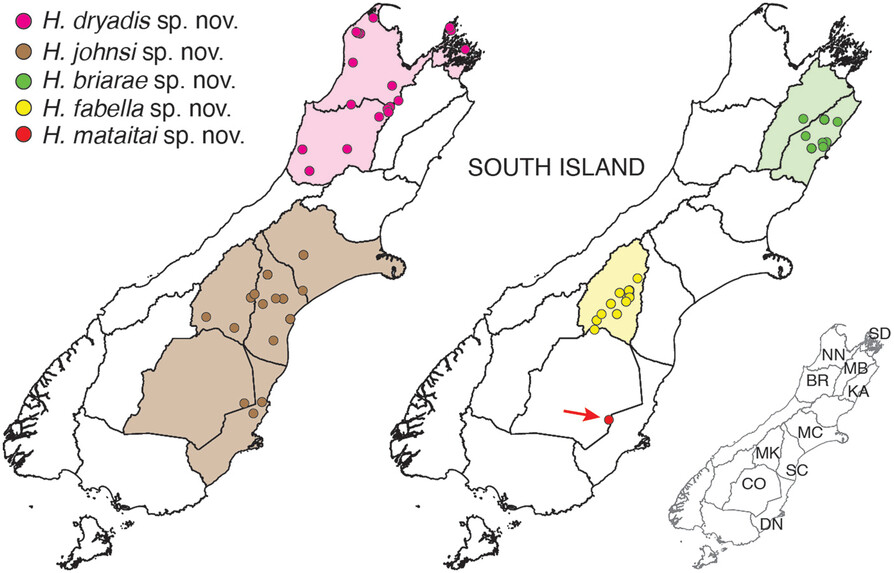

The Hemiandrus group now includes 16 described species with the recent addition of five new names. One of these is the svelte Dryad’s wētā (Hemiandrus dryadis) that lives in native forest habitat in northwest South Island. Orange hued and long-limbed, this species is most similar to Jacinda’s wētā in North Island.

A second large species is Briar’s wētā which is lives in neighbouring regions in northeast South Island, but appears to be limited to high elevation habitat. It lives amongst sub-apline vegetation, which suggests it is cold tolerant and could be freeze-tolerant like other New Zealand alpine insects.

Three other smaller species are from low lying areas in Canterbury and Otago and these include a species associated with the Tekapo river area and sometimes referred to as the. ‘Tekapo’ wētā. This species now has the formal name Hemiandrus fabella, which means ‘little bean’ in reference to its small size and compact shape.

All of these species are threatened by human activities that modify their habitats, and predation by introduced pests such as hedgehogs. In particular the lower lying areas of Canterbury region are subject to ongoing agricultural intensification so the current and future status of H. fabella, H. johnsi and H. mataitai remains uncertain. Biodiversity can be lost before being discovered, and the Sutton Salt Lake wētā H. mataitai , which is known from just one location is an example of the fragility of the situation.

REFERENCES

Trewick SA, Morgan-Richards M. 2026. Five new species of New Zealand Hemiandrus Ander 1938 ground wētā (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae). NZ Journal of Zoology 53:e70007. https://doi.org/10.1002/njz2.70007

Trewick SA, Morgan-Richards M. 2025. Two new species of New Zealand Anderus Trewick et al. 2024 ground wētā (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae). Zootaxa 5666 (3): 408–418. https://mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.5666.3.5

Trewick SA, Taylor-Smith BL, Morgan-Richards M. 2024. Wētā Aotearoa—Polyphyly of the New Zealand Anostostomatidae (Insecta: Orthoptera). Insects 15: 787. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/15/10/787

Trewick SA. 2021. A new species of large Hemiandrus ground wētā (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae) from North Island, New Zealand. Zootaxa 4942 (2). https://www.biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/view/zootaxa.4942.2.4

See: https://evolves.massey.ac.nz/