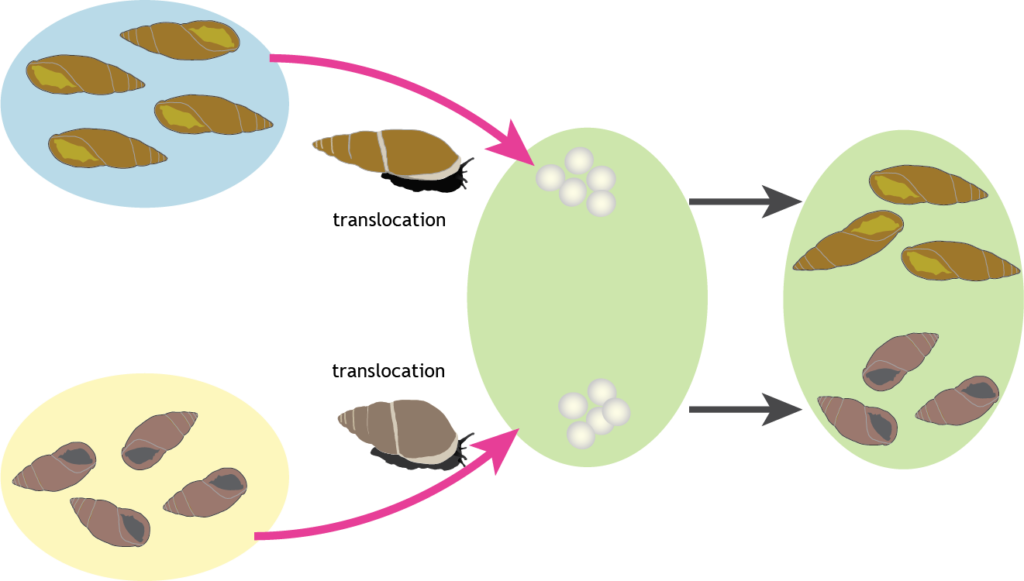

Pūpū whakarongotau (Placostylus ambagiosus) is a large leaf-eating land snail that has declined to fewer than 2000 individuals scattered over 19 populations. These snails are highly valued by tangata whenua of far north Aotearoa (Te Aupōuri me Ngāti Kurī), because in the past the snail was both kai and made alarm calls at night warning of approaching invaders. The sounds these pūpū (snails) make as they hastily retreat into their shells when disturbed at night once alerted the people to approaching invaders and so saved their lives. So, the snails are known as pūpū whakarongotaua -the snail that listens for the war party. Oral histories tell us that snails were moved to propagate new P. ambagiosus populations along with harakeke and karaka.

We know that individuals of this species seldom move more than a few metres from where they hatch, are long-lived (10–22 years), and show strong site fidelity – with individual snails being able to crawl home over at least 60 metres (Parrish et al. 2014; Stringer et al. 2017). The tough shell protects adult snails from native predators and the climate, and preserves evidence from the past.

Visible differences in the size and shape of snail shells of this species (Placostylus ambagiosus) led to numerous distinct isolated populations being given their own subspecies name. Using museum material collected 70 years ago we studied shell shape variation to determine whether it is the result of genetic differences or environmental differences. On a headland, previously the site of a pā (fortified settlement), one population that resulted from prehistoric cultivation of snails showed that shell shape differences are maintained when the snails are living and growing in the same environment.

Using geometric morphometrics of shell shape we could discriminate pūpū shells without reference to where they had been collected. Our genetic data confirmed that some human movement of snails had occurred but that this has not resulted in a loss of genetic differentiation from east to west. We recommend that the shell shape (not size) of these species can be used to infer genetic differences that might be important for the survival of the species as climate changes. All shape variation should be conserved by protecting all living populations from predators and competitors. The subspecies names are a good way to refer to this diversity and protect the evolutionary potential and historic record held in these populations.

Daly EE, Trewick SA, Dowle EJ, Crampton JS, Morgan-Richards M. 2020. Conservation of pūpū whakarongotaua – the snail that listens for the war party. Ethnobiology and Conservation, 9:13(13 May 2020)doi:10.15451/ec2020-05-9.13-1-27