After publishing the species description we realised that we had re-described Celatoblatta undulivitta Walker 1868. We made a mistake – the species that needs a name is the very similar but more widespread in North Island New Zealand. In 2026 we’ll put this right.

The discrepancy between formally described species and the number of species that actually exist is known as the “Linnaean shortfall”. In Aotearoa New Zealand, it is 59 years since the last cockroach species was formally described [Morgan-Richards & Trewick 2025]. Some might think that another cockroach is the last thing we need but taxonomic knowledge of all dimensions of life on Earth is critical to cataloguing, measuring, and understanding biodiversity. Biodiversity exists and documenting it is critical, but taxonomy is a field without funding.

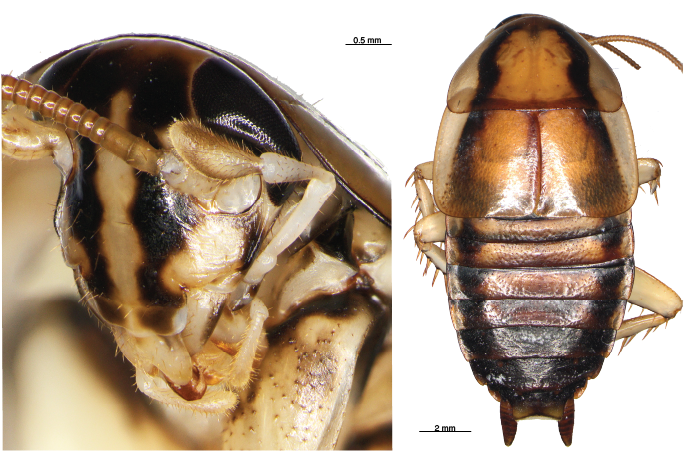

A new species of forest cockroach endemic to Aotearoa New Zealand is more than just one new species we need to save from extinction. This insect (~ 15mm long) is home to its own species-specific Blattabacterium endosymbionts; an ancient heritage of the cockroach-termite lineage dating back more than 200 million years. These bacteria live only inside body tissue of each cockroach and contribute to its survival. In addition, like other animals including humans, each cockroach hosts a novel community of microbes in its gut.

The new kauri cockroach Celatoblatta kauri just described is almost certainly the host of unique Blattabacterium and other forms of micro-biodiversity. These particular organisms are restricted to northern New Zealand where kauri forests grew before humans arrived. Each time we name a new species we create the words needed to describe the intimate associations between host and microbe.

The practice of coining a Latin binomial to apply to a newly described species has consequences for the science we do, influencing its resourcing, its public communication, and sometimes even the direction of research. The lack of support for taxonomy and the resulting slow rate of species discovery and description is a phenomenon referred to as the ‘taxonomic impediment’. Naming biodiversity should be a priority in conservation biology because until we know what we have we do not know what we are trying to save.