Fossil snails might tell us of the frequency of heavy rainfall in the past

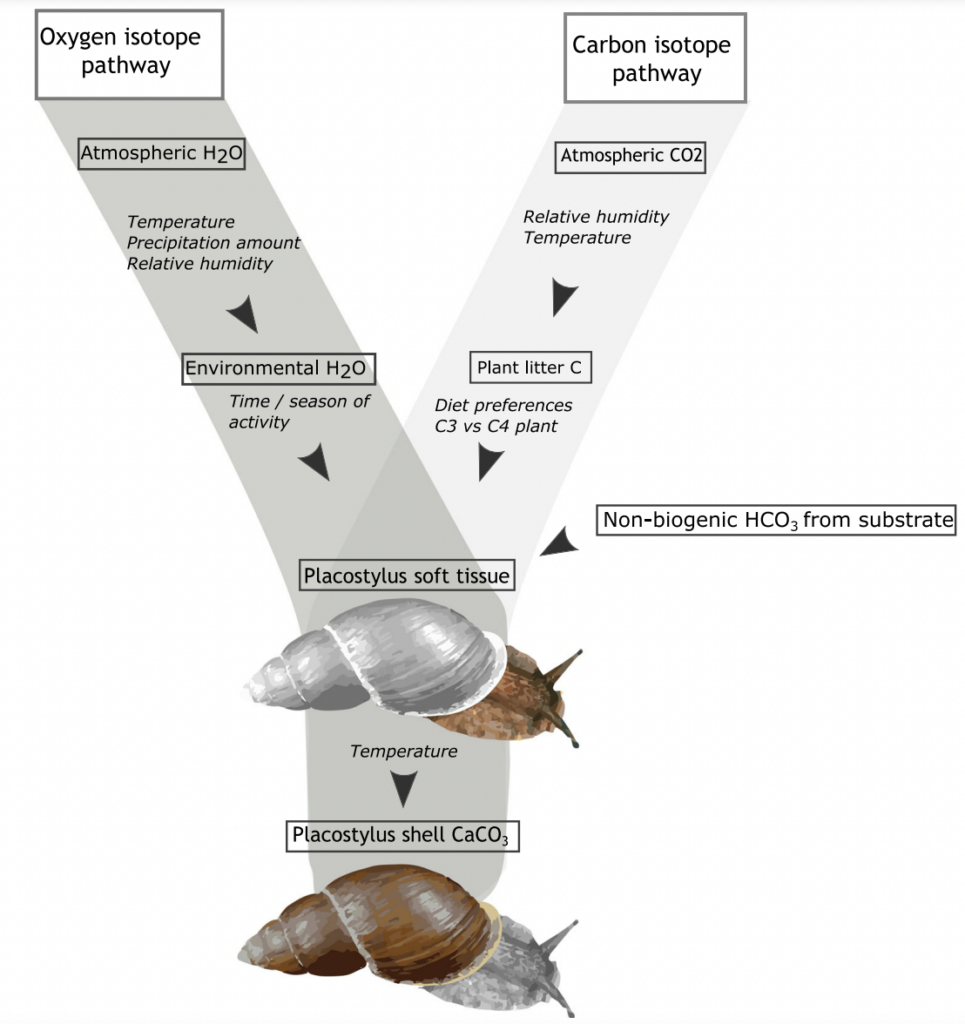

A new study comparing the stable oxygen and carbon isotope ratios of giant land snails in New Zealand and New Caledonia found a surprising result. New Zealand snails had, on average, higher oxygen isotope ratios values than their counterparts in New Caledonia, counter to the relative isotopic composition of rainwater between these two regions. This research just published in the Journal of Quaternary Science provides baseline data for using the shells of Placostylus snails as environmental proxies – allowing us to use fossil shells to estimate the temperature and rainfall when the snails were alive.

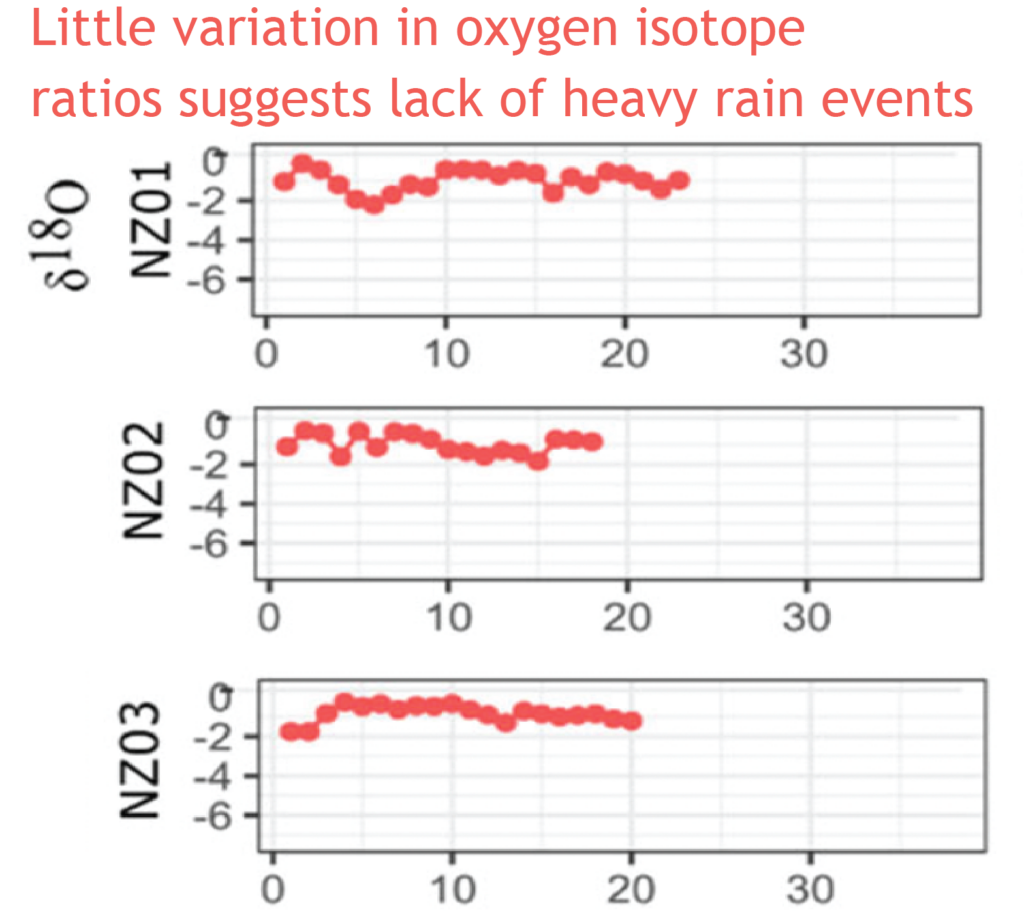

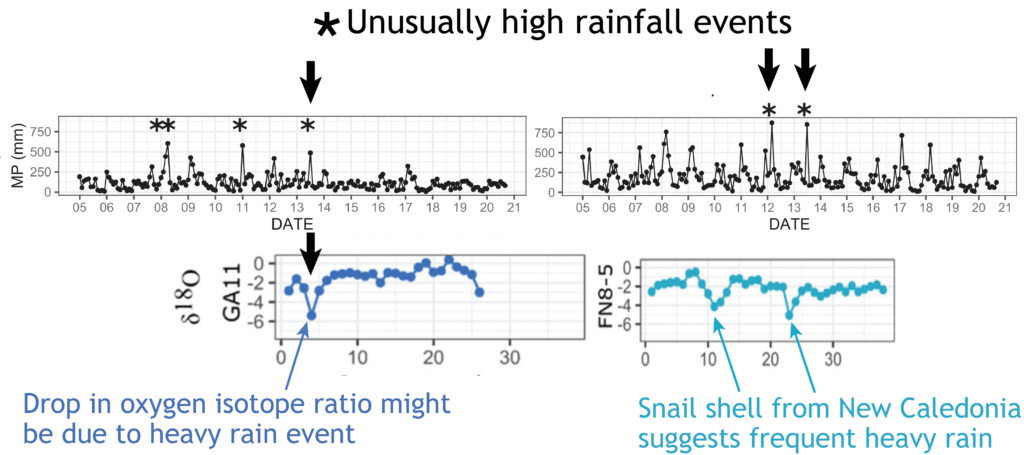

contrasting patterns between snails originating from New Zealand and New Caledonia

Most interesting are the dramatic drops in oxygen isotope ratios that seem to correspond to heavy rainfall – suggesting an opportunity to dig into the past to compare past precipitation with current frequency of wet weather events in New Zealand. There is also the potential to study the frequency of droughts from the pattern of snail shell growth.

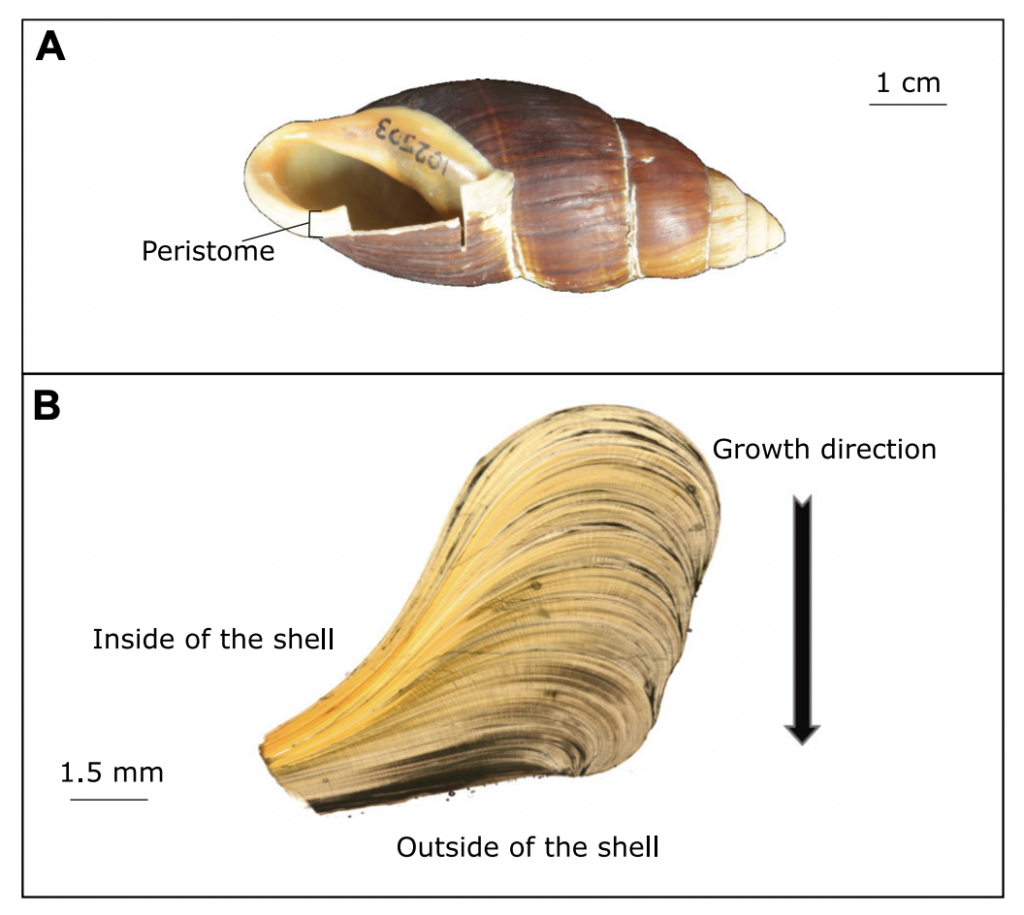

Scientists at Massey University and NIWA sliced up shells of three species of giant land snail (pūpū whakarongotaua; Placostylus). The recent samples from New Caledonia showed drops in isotopic values in their high‐resolution profiles probably linked to periods of intense rainfall.

Very heavy rainfall events produce lower stable oxygen isotope ratios incorporated into the shells of the living-growing land snails. In contrast, the snails from New Zealand varied very little, suggesting that when they were alive, 74 years ago, there were few heavy rain events in the Far North of New Zealand.

The snails (pūpū whakarongotaua; Placostylus) are taonga of Ngāti Kurī who value them as security alarms (the snail that listens for war parties). Ngāti Kurī are working to save the local species from extinction but they are also kaitiaki (guardians) of fossil shells buried in the sand dunes and stored in museums. These fossil deposits could provide information about the past climate through high‐resolution stable oxygen isotope profiles.

“it is exciting to think of all the information locked up in snail shells – the shape of the shell, the DNA and the isotopes can all tell a story about the past” said Mary Morgan-Richards. “As Placostylus snails are slow growing, taking 10 years to reach maturity, and live for a long time, they can each tell their own story. There is much to be learnt by digging into old shells to reveal the frequency of heavy rainfall events in the past.”