Bloody, funny – the golden age of NZ crime fiction

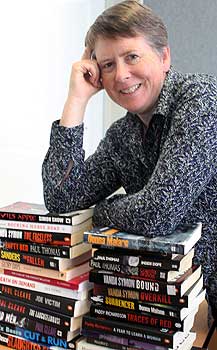

Dr Jenny Lawn, from Massey University’s School of English and Media Studies.

Blood-soaked with a vein of humour. These are the distinctive features of home grown crime fiction, which has soared in popularity over the past two decades, says an academic who’s read most of it.

In fact the past 20 years have been dubbed ‘the golden age of Kiwi crime fiction’ by Massey University New Zealand literature expert, Dr Jenny Lawn, who has just penned a chapter on recent trends for a forthcoming edition of the Oxford History of the Novel (Oxford University Press).

Having ploughed through over 40 blood-drenched, sinister-themed books by 20 authors, she is struck by the “sheer proliferation” of crime fiction here.

Before Paul Thomas, who started to publish in the 1990s, our main crime detective writer was Ngaio Marsh. “Nobody came close to equalling Ngaio Marsh in terms of success except for [the late] Laurie Mantell,” says Dr Lawn, who teaches New Zealand literature and media studies papers at Massey’s Auckland campus.

Mantell, who worked as an accountant in Lower Hutt and died aged 93 in 2010, wrote five detective novels in the late 1970s and early 1980s all set in and around Wellington, and had an international following. Marsh, on the other hand, was an anglophile who set the majority of her 32 novels in Britain.

Paul Cleave, New Zealand’s most internationally acclaimed crime writer since Ngaio Marsh, has an international following in France and the United States. His first book The Cleaner (2006) has sold over a quarter of a million copies.

“All of Cleave’s seven novels are set in his home city of Christchurch, which breeds evil as refuse breeds flies: the picturesque Avon River is a cesspit of urine, weed, and used condoms; the Port Hills are regularly cordoned off where ‘some poor kid is being peeled off the asphalt’ (The Killing Hour),” she writes.

For a blood-spattered, high body count, you can’t beat Cleave’s 2010 grisly thriller Blood Men, says Lawn. So it’s no surprise he has apparently had people come up to him at overseas literary festivals saying they won’t be visiting New Zealand after reading his books, she says. Crime fiction, by the likes of Ben Sanders and Chad Taylor, is typically set in urban environments; “often in the seedy part of town, also linking the wrong side of tracks to the right side of tracks,” she says.

“You have the salubrious leafy suburbs or corporate downtown mirrored sky scraper feeding off, or trafficking into, the down and out suburbs. You have the social ecology of crime in these novels.”

Character in New Zealand crime fiction is efficiently sketched, says Lawn, sometimes through wise-cracking one-liners, like the portrayal of Bryce Spurdle in Paul Thomas’ Inside Dope; “watching [him] eat was like watching a paisley shirt in a tumble dryer.”

Kiwi crime authors freely extend conventional genres, creating hybrids by grafting detective elements onto romance, historical and domestic fiction. Unlike the 1930s and 40s American hard-boiled, loner detective, the New Zealand detective is “typically self-deprecating or self-doubting” and more likely to work in a team.

Largely missing is the figure of the femme fatale of early American crime novels. Instead, the amateur female sleuth is out in force in many a Kiwi crime book, her presence rendering the femme fatale irrelevant, Dr Lawn says.

When it comes to murder weapons, Kiwi authors are distinctively quirky. “Guns are generally shunned in favour of more improvised methods of disabling the criminal, such as a frying pan, spade, bronze horse sculpture, can of aerosol fly spray, or strategically-inserted wireless telephone aerial,” she notes.

Does she think this murderous literary trend offers any insights into our national psyche?

It might reflect a growing distrust of police by some, she suggests. “Many crime novels now have a corrupt current or former police officer as one of its investigators. It’s become part of the genre to have a compromised investigator teaming up with a straight or protocol-obeying member”.

“One of points of genre fiction is that you are writing for a market, so you’re thinking about what out there is of interest to people. It’s writing for the market rather than ‘how do I want to express myself?’”

“When writing for a market you are probably tapping into existing social desires, picking up on a vibe. It’s often said that genre fiction is a better index of popular interests and desires than the more elite, high-brow novels”.

Dr Lawn’s article also gives an update on the genres of sci-fi and political dystopia, and notes the emergence of newer literary species such as paranormal romance, steampunk, and eco-dystopia.

These are all hopeful signs at a time of retrenchment and general gloom in the publishing industry, she says, with e-book, self-publishing and fan sites supporting new niche genres and the “plurality of voices, identities, genres, and audiences” they cater to both locally and globally.

Related articles

Academy puts spotlight on humanities research

Sex worker story to prize-winning play

Ihimaera winner in Māori book awards at Massey

‘Bookcrossing’ spreads word on learners with differences