“El arte es un respiro espiritual e inmaterial de las dificultades de la vida.”

(Fernando Botero, Museo Botero, Bogotá.)

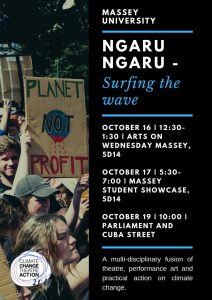

To world-renowned Colombian artist Fernando Botero, who donated more than 200 pieces of his own and others’ art (Picassos, Monets, Dalis, and more) to the people of Colombia in the year 2000, art provides a respite, an escape from life’s challenges. Yet, as eight Massey University Expressive Arts students and two staff members from the School of Humanities, Media and Creative Communication who travelled to Bogotá as part of a month-long New Zealand Prime Minister’s Scholarship group in April-May 2023 discovered, in Colombia art is far more than just sanctuary – it is also protest, provocation, and proclamation.

Massey Expressive Arts students and staff with Universidad de Los Andes students at the Museo Botero, Bogotá. (Back L to R) Professor Elspeth Tilley, Massey PMSLA scholarship students Luciano Lara, George Wilson, David Robertson, Irihapeti Moffat, and Jesse Brady, Professor Leonel Alvarado, (Front L to R) Massey PMSLA scholarship student Chris Parkinson, local hosts Juan Pablo and Miguel Nicholás, and Massey PMSLA scholarship student Samantha Carter.

Psychologist and theatre maker Mariana Parejo, who was one of the Universidad de Los Andes staff working with our Massey group, told us, “In Colombia we have seen a lot. We have seen war, conflict, and violence. Now, we have been working to overcome this history and move forward in peacetime. This process has made us recognise the incredible power of art to heal and to create change.”

The streets and communities we visited in Bogotá, and the people we worked with, proved Mariana’s words: on every side we saw art agitating and advocating, giving voice to new ideas and unheard perspectives, and building caring communities. We were also incredibly fortunate to be invited to work collaboratively with some of these artists, to generate a new work about climate change, an issue that the two countries, Aotearoa and Colombia, share a sense of urgency about.

We have space only to list some of the remarkable examples of creative activism we encountered or were lucky enough to participate in, but here are a few highlights.

Music

Everywhere in Bogotá, we heard music. From the tinny speakers blaring cumbia drums and accordions from every street vendor’s cart, to spontaneous drum groups outside our student accommodation at night, to the Vallenato band that jumped on the passenger train we were riding and serenaded us with guitars and flute, to haunting tones of Totó La Momposina, considered the ‘first lady’ of Colombian folk music, to the irresistible dance beats of ChocQuibTown hiphop, music was all around us, infectious, and passionately activist.

Totó’s ‘El Pescador’, for example, pays homage to the humanity of impoverished fishermen who may have “no fortune, only their net” but brave the rising currents to bring the catch home to their loved ones. ChocQuibTown’s De Donde Vengo Yo (which won a Latin Grammy) is a powerful and catchy protest song decrying the exploitation of Colombia’s gold and platinum wealth by multinationals and corrupt politicians.

If you’re interested in learning more about the music we encountered, one of the students in our group, Chris Parkinson, has a show on ArrowFM where he is sharing insights into and samples of Colombian music. Check out the podcast at https://www.arrowfm.co.nz/programmes/show/229/waibrations/

Graffiti

Since a 2011 law change to decriminalise graffiti in Bogotá, the city has become world famous for its street art which runs the gamut from sky-high tagging at the top of an unfinished skyscraper to beautiful murals depicting the people, stories, and culture of Colombia.

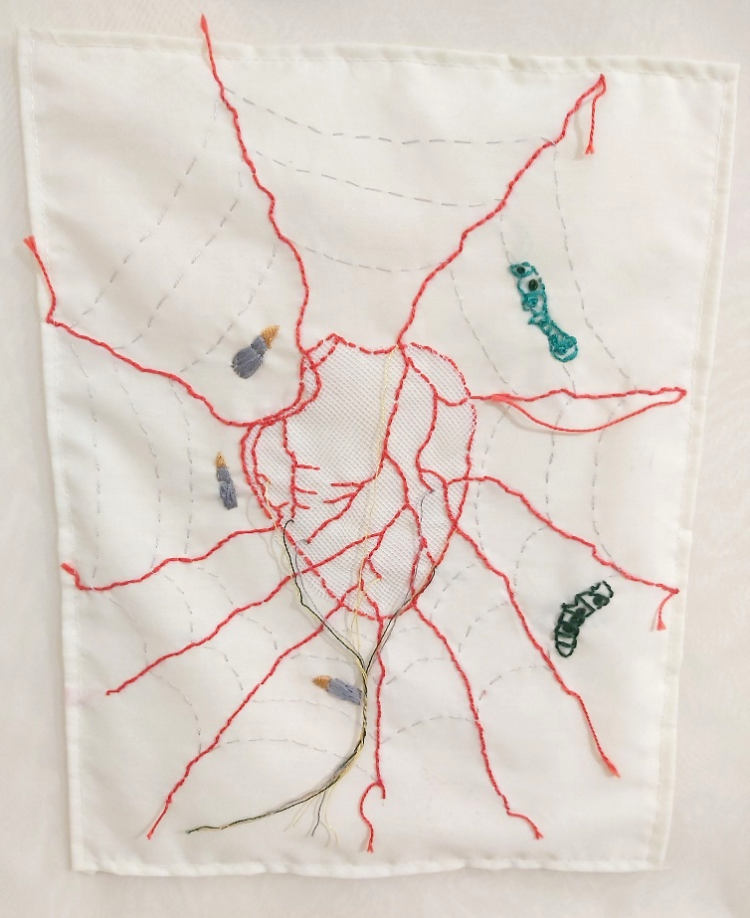

We joined a guided tour with Capital Graffiti and our host Luis explained how decriminalisation has lifted the quality of artwork in the city, creating a tourist attraction and leading to professional mural work for the best artists. All of the artworks Luis showed us had activist intents, some obvious and some subtle, from advocating for women’s rights to revitalising the stories of particular Indigenous groups. Other street art was just as political – for example the incredible building-high quilts shown in our opening photograph (taken by George Wilson), which are part of a seven-year-long craftivism project by women peacebuilders intended to inspire hope and healing.

Fragmentos

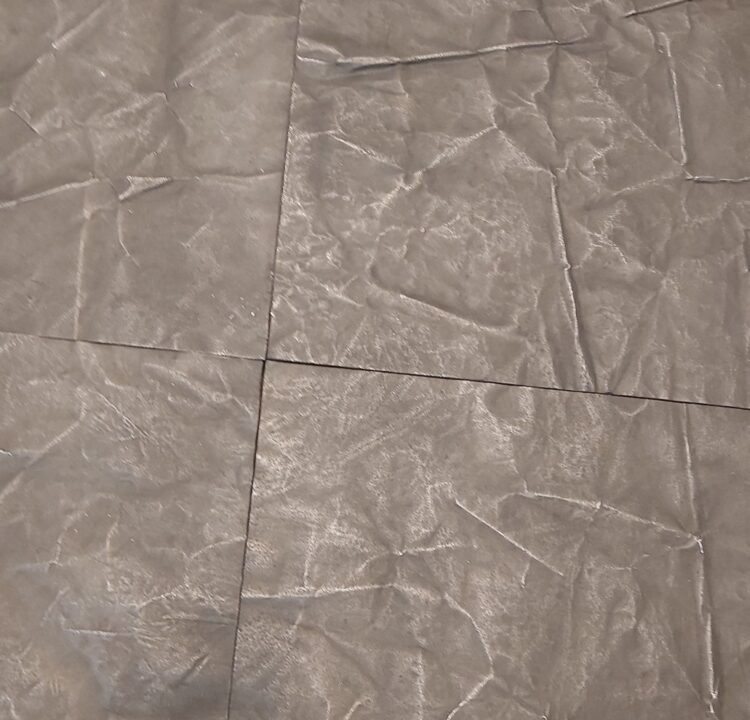

We had daily Spanish language lessons at Universidad de Los Andes, building on our study undertaken in the Spanish programme at Massey before departure. Towards the end of our stay, our Colombian Spanish teacher Johana Lopez took us out of the classroom to tour the city using our language skills to navigate and describe what we saw. The tour culminated at the Museo Nacional de Colombia’s installation art venue Fragmentos – Espacio de Arte y Memoria (Fragments – Space of Art and Memory). There we encountered a striking and confronting “contra-monument” by distinguished Colombian sculptor Doris Salcedo, consisting of floor tiles constructed from thirty-seven tons of decommissioned guns surrendered during the peace process.

We learned that the guns were melted down and hammered into tiles by women who were assaulted during the conflict, who collectively shared their rage at what had happened to them by working together to beat the metal into ridges, ripples, and scars with heavy hammers. We walked and sat on the gun-panelled floor as our guide issued us with a powerful invitation to reflect on the 50-year armed conflict in Colombia, its pain and costs, and the role of art in reconciliation and healing.

La Esquina Redonda

One of the most special and moving opportunities we received in Colombia was to work with members of La Esquina Redonda, an artistic collective of people originally from a district called ‘The Bronx’. We first visited them in a collaboration space called ‘Espacio Tejido’ (Woven Space) at the Museo Nacional de Colombia where they now work, both as artists and as museum guides, and they told us their stories. They had lived in The Bronx, often for years, and it was their home, but in 2016 the district was bulldozed by the authorities as an anti-narcotics measure, leaving everyone homeless. Many of the young people were put into protective custody institutions. A community worker, Susana Fergusson, who has dedicated her life to reducing the harm caused by drug abuse, found a new community space for the young people, calling it the new Bronx Distrito Creativo (Bronx Creative Space), and started a programme using art and creativity to teach those who had been displaced new skills and help them generate a new vision of their lives.

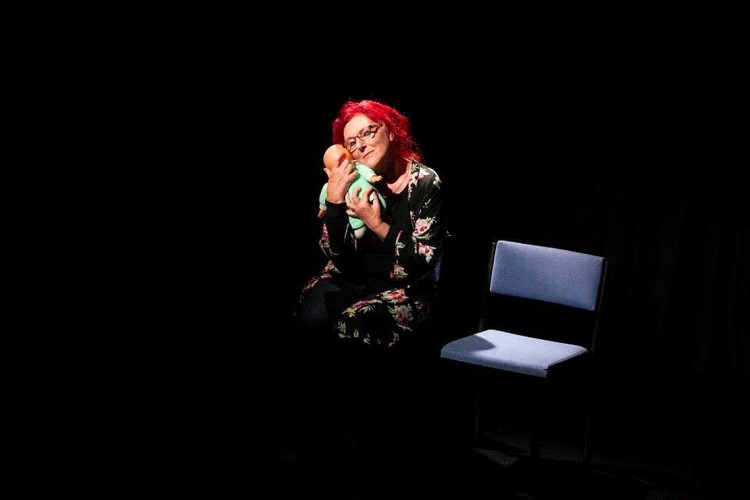

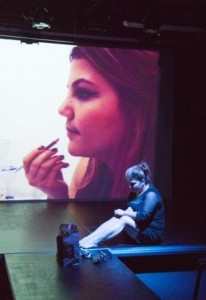

After hearing powerful, and sometimes heart-breaking, stories from the members of La Esquina Redonda, in return the Massey students shared a theatre performance we had rehearsed in Aotearoa that explored Indigenous relationships to water. Using theatre as a means of connecting across cultures, we discovered deep connections between Māori worldviews and the worldviews of Indigenous Colombian groups. The sparks of collaboration were born, and over the next four weeks under the direction of Mariana Parejo, both groups worked together to craft a multifaceted collaborative theatre piece exploring ideas of rivers, water, and sacred relationships to the Earth. This culminated in a shared performance called ‘What if the River Could Speak?’ in the Auditorio Alberto Lleras Camargo, Universidad de Los Andes.

The shared performance was an opportunity to put the connections we had discovered between our richly biodiverse regions, our Indigenous cultures, and our artistic traditions into action to cocreate a powerful piece of creative activism.

Together, we crafted stories that call for a new understanding of climate change as a shared problem that effects all of humanity and reimagined the Earth as a sacred space that we have no right to exploit. It was a fitting conclusion to our month in a place that showed us rallying, powerful artworks of healing, compassion, and protest around every corner.