Writing an internationally acclaimed essay on the feminist themes of gothic novel Frankenstein may not be typical of how mothers spend precious evenings when their youngsters are in bed.

But for Helen Peters – Bachelor of Arts graduate and mother of four – immersing herself in writing about the social significance of a story about a mad scientist and his monster was bliss.

She graduated from the College of Humanities and Social Sciences (in absentia) last week and says being able to combine her passion for studying literature and history with motherhood was demanding but well worthwhile – for her personal fulfilment and being a role model to her children. The way she calmly deals with intermittent requests for rice crackers, ‘Gwain-Waves’ and drinks of water while discussing her intellectual life is evidence of her juggling panache.

Helen began her degree by distance three years ago by enrolling in one paper when she was living in Australia with four small children underfoot.

“I chose Massey because I could do it extramurally and I’d heard really positive things about the distance programme from friends,” she says.

She got an A+ for her first paper on Academic Writing, which boosted her confidence and encouraged her to continue studying.

Graduating is a milestone but being awarded a prestigious Highly Commended Undergraduate Award from the Ireland-based organisation was a highlight last year. She was one of four Massey BA students (the only ones from any New Zealand university) to receive the honour, after Massey lecturers impressed by her writing urged her to enter.

Discovering Frankenstein during a Gothic literature paper was a revelation that led to her award-winning essay. She’d had preconceived ideas about it from movies and popular culture. “I thought of it as a man with bolts in his head and a crazy scientist – a story that’s all about men. It is narrated by a man but it’s actually about women, and women’s place in society as the moral compass,” she says. “If you try and ignore this – like Victor Frankenstein does when he creates his monster – it leads to chaos and the breakdown of relationships and family. It was written in the 1800s by Mary Shelley, who grew up without a mother.

“I will never read another book again without seeing so much more – even one paper opens your world.”

Parenting and study?

The key to studying with young children, she says, is to have a great support network.

“It’s essential that you have someone who understands that you need that time to study, and also to reflect on what you’re studying as well – it’s not just reading something out of book and then regurgitating it. You’ve got to have that time to think it through and process it.”

Her husband Carl is her main support. “He jokes he’s supporting me so that one day I’ll have an awesome job and be able to buy him fancy golf clubs!”

Helen treats the time her kids are at school as her working day, from 9am to 2.30pm. From 7pm to 9pm, her husband helps by cooking dinner, bathing and putting children to bed.

“Even though all I wanted to do at the end of the day was curl up on the couch and watch TV, I would study while they were in bed.”

Her advice for students with young kids? Find that time of day that works best for you to study. If you do not have a partner as support, maybe extended family or friends can take kids for a few hours, she says. “Don’t be afraid to ask for time to study. It’s not selfish to ask for help – remember that the end result will benefit everybody.”

Another key to success in studying with kids is that “you have to have that real passion and drive for it,” says Helen, who wants to be a role model for her offspring, aged ten, eight and twins aged six. “When I’m studying I say to them ‘you can see mum making a big effort – one day you will go to higher education too’.”

Social history of maternity homes for unwed mums

With a BA under her belt, Helen plans to follow her passion for New Zealand history to do a master’s thesis on the oral histories of women in the mother and baby homes of the 1950s, 60s and 70s – a topic that has had little attention to date. She wants to examine how women were treated in these homes, inspired after seeing the 2009 New Zealand film Pieces of My Heart.

“As the tide of social mores was turning in 60s when birth control became more readily available, attitudes started to shift from conservative ideas about unmarried mothers into the attitudes we more or less see today,” Helen says.

“It’s no big deal having a baby out of wedlock today. I want to look at that era and have something tangible for those women to show; ‘this is what happened to me’ – for others to know about.”

While she senses some might question; “Why dredge up sad stories?” Helen believes women spend so much of history on the side lines. “There’s so much about women that the history books don’t record because they are more focused on men. Yet the history of women can tell you so much about the prevalent attitudes of society.”

She wants to find 20 women to interview who were accommodated in maternity homes around the country. “Girls would be sent ‘up north’ and come back seven months later, and nothing else was said. It was hushed up because of shame. As women, we want to talk about these big things. It would have been exceptionally painful to have had and held her baby and had it taken away, then go away and never talk about it.”

With her sights set on becoming a full-time academic engaged in teaching, research and writing, Helen believes the study of history – and humanities and social sciences in general – is vital.

“As a historian I think we live in extremely exciting – or interesting – times right now. You’ve got Trump, North Korea and more – one day I think people will look back at this time and think ‘what shall we read to understand what was happening?’.”

Her academic goals and dreams have evolved since she first began her BA journey, enrolling straight out of school in a law and arts degrees at Victoria University, eventually deciding law was not for her, but that she loved history. Helen studied on and off for two years until she moved north to be near her parents to catch her breath after a difficult relationship and mental health issues (post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety).

Her life direction changed when she met her husband, got engaged and pregnant, resuming study with a new sense of direction and a growing family.

Love for the BA

Helen is a keen champion of the BA, despite the negative attitudes she’s encountered. “There’s this feeling that a BA is just fluffing around reading books or sitting around talking about poetry. What people don’t realise is that it teaches you to critically think about people and society.”

She believes it is important we have people who can “read books, peel back the layers and see what a novel is saying about society. And people who study history – imagine if we didn’t record the Nuremburg trials after WW II and any other atrocities? All of this is important. Engineering helps to build things, but it doesn’t tell us about what society is like.”

She sees plenty of fertile areas for further research and envisages herself writing history books on “byways” of New Zealand history, including the lives of women as criminals, and women in mental health institutions. In her own family, a relative was put away for her ‘uncontrollable rage’. “What is that exactly? How many women were put away to be out of their husband’s way?”

Studying history has the potential, she says, to spark interest and awareness about tricky areas of our past and to track social change. “Women are expected to be silent – you have a baby and it gets adopted out and you can’t say anything. Or somebody gropes you at work and you have to be silent if you want that job.”

That’s why the history of women is her focus. “It’s a real privilege to do a masters and give a voice to these sorts of silences.”

Helen exemplifies what’s achievable for mature students with families. Her children enjoy coming to the Manawatū campus library to help her carry books, as well as the enriching conversations her study sparks on diverse topics and ideas.

Nurturing the life of the mind is essential counter to the everyday challenges and busy-ness of family life. “When I sit down at my computer and start writing I feel ‘I just love this!’.”

(Helen graduated in absentia due to the logistics of family life, but plans to cross the stage to be capped for her masters).

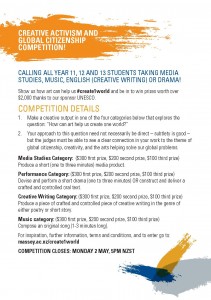

all creative rangatahi! We know you have great ideas about how to make the world a better place. Turn them into a short film, poem, story, song or piece of theatre, and you could win cash prizes. Check out http://sites.massey.ac.nz/expressivearts/create1world-2020/ for all the details of the 2020 Create1World Competition. It’s NOW OPEN and you have until June 2, 2020 to get your entries in.

all creative rangatahi! We know you have great ideas about how to make the world a better place. Turn them into a short film, poem, story, song or piece of theatre, and you could win cash prizes. Check out http://sites.massey.ac.nz/expressivearts/create1world-2020/ for all the details of the 2020 Create1World Competition. It’s NOW OPEN and you have until June 2, 2020 to get your entries in.