Impact Factors, Eigenfactors, SNIPS and Other Partial Measures

October 4, 2013

Zombie bibliometrics

There are three common misconceptions about journals and research evaluation that don’t seem to want to die, no matter how often angry mobs shoot at them with silver bullets or drive a stake through their hearts. Like many persistent fallacies, however, they are difficult to kill because they bear some relation to the truth, and getting angry about them or saying that they should be banned probably probably isn’t going to cut it. They are a sort of Fast Truth, simple, quick and tasty, not to mention cheap, and for busy administrators they offer a convenient substitute for the slow and difficult business of thinking. Here they are –

1 The Quantitative Half-Truth – Every scholarly journal has an Impact Factor and journals can be compared with one another by comparing these numbers.

2 The Qualitative Half-Truth – There is a ranked list of journals which assigns to each and every title an A, B or C ranking to each one based on the opinion of expert panels.

These in turn give rise to

3 The Cart-Before-the-Horse-Fallacy – It is possible to assess the academic standing of an individual researcher or a department by looking at the journals in which they have published according to these ranking systems.

Today I’m going to have a look at the Quantitative Half-Truth and the Cart Before the Horse Fallacy, and we’ll come back to the Qualitative Half-Truth in a later post.

The Quantitative Half-Truth. Yes, there is such a thing as a Journal Impact Factor and it is a number that is often used to compare journals. Journals that are indexed by the Thomson Reuters database Web of Science (WoS) are assigned an Impact Factor (IF) by Journal Citation Reports (JCR) on the basis of how often in a given year their articles from the two previous years are cited. It is a simple numerical calculation that says that if the Journal of X published 15 papers in 2010 and 20 papers in 2011 and these 35 papers are cited 70 times in 2012 by other articles within the Web of Science then the Journal of X has an IF of 2. Like the h-index it is pretty easy to understand and it does sort of mean something in a rough-and-ready rule-of-thumb looks-pretty-good-to-me-Norman kind of way. Nature and Science get an IF of about a gazillion and the Manawatu Journal of Research Metrics* gets an IF of 0.000001 (hey, we go for quantity over quality) so you know where you want to publish, right? So far, so good.

Things begin to get tricky …

The Impact Factor does a pretty good job of telling us that certain really well-known journals are, erm, really well known and that other are less so, but to what extent is it a one-size-fits-all universal measure of journal quality? Things begin to get tricky when we get to the business of coverage. Because the IF is calculated for journals within that select group of titles indexed by WoS, only those journals have an official IF. In theory it is possible to calculate a WoS-based IF for non-WoS journals but this would be a lot of work and there is no way that Thomson Reuters, who own WoS and Journal Citation Reports, would allow you to publish a list. In any case, to give comparability with the WoS IFs the citations on which the calculations were would still have to be sourced from WoS, so essentially control over which journals get an “official” or “unofficial” IF number belongs to Thomson Reuters. Now, in some disciplines this isn’t going to matter too much. Although it covers a wide range of disciplines Web of Science, as its name implies, has excellent coverage of science and in many areas there are few or no significant titles which it doesn’t cover. Effectively this means that if a journal does not have an IF then it is not really a player in the scientific community, and also that the citations used to make up the IF all come from journals that do have a real and meaningful existence within that community. However, once we move beyond this scientific core, coverage is a lot more patchy and plenty of perfectly good journals from the social sciences, business and humanities don’t appear in WoS and therefore don’t qualify for the magic IF number. Because WoS has a preference for titles from the large established publishers (Springer, Elsevier, Wiley) this impacts particularly on journals from smaller publishers, learned societies and so on. What is more, in the humanities (where citation rates tend to be lower) most titles are not even processed by JCR by so again there are no official IFs for many significant journals.

Everything is not the same as everything else …

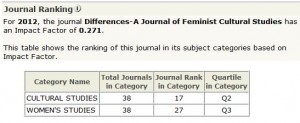

This leads us to another question of course, which is the variability of citation rates between disciplines and the fact that a raw number in itself conveys almost no useful information until it is measured against the normal expectation for the relevant research field. Journal Citation Reports does this by assigning the titles it evaluates to categories and then ranking them within each category by Impact Factor. What really matters here is the quartile the journal falls in within its subject area, so that a Quartile 1 (Q1, top 25%) is perceived as having considerably greater impact than a Q4 (bottom 25%) title. You can see in this example that the IF of the journal Differences places it in the second quartile (i.e. between the top 25% and 50%) in Cultural Studies, but in the third quartile (50%-75%) in Women’s Studies where average IFs are higher.

This contextualisation gets around the uncomfortable fact that there are at the moment exactly 163 Cell Biology journals with a higher IF than the “best” Marine Engineering title. (Nothing wrong with Marine Engineering, there just aren’t many marine engineers around to cite one another and by and large they are probably too busy doing marine engineering to publish much.) But journal editors and publishers don’t worry too much with niceties of this sort and if the raw IF figure looks good they are going to splash it around on their website without too much regard for context.

Another common criticism of the IF, as of any simple citation counting measure, is that it allots a simple value of 1 to every act of citation, whether it comes from the most influential author writing in the most highly cited journal or from, how does one put this delicately, someone who is not the most influential author writing in the most highly cited journal. Thomson Reuters attempts to compensate for this deficiency through a couple of more complex analytical tools, the Eigenfactor and the Article Influence Score, both of which assign greater value to citations from more influential sources. This is not really the place to go into the merits of these approaches, but the point to note here is that although they may be more sensitive measures than the Impact Factor they have not yet overtaken it in the popular imagination – using that term in rather a specialised sense.

The other guys …

There are alternatives to the Impact Factor and the best-known of these are two measures based on the journals indexed by the Scopus database. The first of these is the SCImago Journal Ranking (SJR) and like the Eigenfactor it addresses the problem of all citations conveying an equal value regardless of where they occur. To calculate the SJR, numbers journals are given a weighting according to their prestige (the mathematics of how this is done is not entirely clear to a simple mind like mine, but if you’re happy with iterative algorithms then you can read the original paper on which it was based here) and then they dole out equal amounts of that prestige to all of the other journals that they cite. This is intended to even out differences between citation frequencies in different fields, as journals that do a lot of citing have a smaller amount of prestige to attach to each citation. A full list of SJRs can be seen here on the SCImago website and as an example here is the list for Religious Studies. You can also find the SJR for a journal by using the Journal Analyzer on the Scopus database.

The other measure is rather easier to get your head around because it doesn’t involve any fancy iterative algorithms, just a couple of bits of long division. It is the Source-Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP) which “measures contextual citation impact by weighting citations based on the total number of citations in a subject field. The impact of a single citation is given higher value in subject areas where citations are less likely, and vice versa.” For a given field in a given year, citations of articles from the previous three years are aggregated and then divided by the number of total number of papers in the field to calculate the “citation potential” of an individual paper in that field. Then for each individual journal the average number of citations per paper (i.e. the Impact) is divided by the citation potential to produce the SNIP value.

Citations in the Present Year of All Papers in a Given Field for the Previous Three Years ÷ Number of Papers in That Field for the Previous Three Years = Citation Potential for a Paper in That Field

Citations Papers in the Present Year of Papers in Journal X for the Previous Three Years ÷ Number of Papers in Journal X for the Previous Three Years = Impact of Journal X

Impact of Journal X ÷ Citation Potential of the Field = SNIP of Journal X

If a journal has a SNIP of more than 1 then it is cited more often than the average for its field, while a value of less than 1 means that it is cited less often than the field average. This is quite a handy measure because although lacks the do-it-yourself simplicity of the Impact Factor it does give you meaning-at-a-glance usable information – is this journal cited more or less often than others in its field? You can find the SNIP for a journal by using the Journal Analyzer on the Scopus database.

So why not use them instead?

There are some good reasons for preferring these Scopus-derived metrics to the Journal Impact Factor that comes out of WoS. Firstly, Scopus simply covers more journals than WoS so your chances of finding a metric for a given journal tend to be higher. The pool of journals out of which citation data is taken is also larger so, in theory at least, it should give a truer reading without getting into the fantasy realm of Google Metrics. Added to this, the fact that an attempt is made to allow for discipline-specific citation patterns allows comparisons to be made between journals in different areas and for anyone to make a rough estimate of the standing of a specific journal without having to look closely at other titles in the field. That said, though, there is no immediate evidence that the SJR and the SNIP are about to knock the IF off its perch as the preferred journal evaluation metric of the scholarly community. The Impact Factor was first in the field and has just the right combination of high recognition and (apparent) transparency to make it the number that everyone knows about. In many areas, particularly in the sciences, the fact that it doesn’t cover all the journals is of no great importance because it covers everything that working scholars are likely to refer to and there is no practical advantage in using the Scopus figures. Titles like the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, for example, make a big deal of their Thomson Reuters (i.e. WoS) numbers and rankings without mentioning the Scopus figures at all, as you can see here. Even Elsevier, owners of Scopus, give at least equal ranking to the IF for their own prestigious title Animal Behavior (here) while for their title Acta Astronautica the Scopus figures are simply left out (here). In any case, the figures from the SJR (Scopus) and IF (Thomson Reuters/Journal Citation Reports) tend to be pretty similar – if we look at the top ten titles for Horticulture in both lists (JCR and SCImago) there are eight shared titles and the main differences are often the categories to which titles are assigned, with the categorisation of JCR being rather more fine-grained.

So what’s the point?

So anyway, is there any point to all of this obsessing about the numbers attached to the rather opaque and esoteric business of scholarly papers referencing other scholarly papers? Journal editors and publishers naturally like to brag about their metrics if they are good, and agonise over them if they aren’t, and they have been known to engage in nefarious schemes to rig the figures, and librarians sometimes look at them if they are asked to subscribe to a journal, but is there any reason for busy and hardworking researchers to take any notice of them? Actually there is one very good reason, and that is when deciding on whether to publish in a particular journal, or when choosing between a number of journals in which a piece of work could be placed. The fact that Journal X has a track record of being cited twice as often as Journal Y suggests at the very least that it is more widely read, that its articles are taken seriously and that researchers “like” citing them. (There is a psychological component to all this that can’t entirely be ignored.) The converse is that a journal that is very infrequently cited has not yet built a reputation, that its articles are not widely available and that it is not taken seriously by the relevant scholarly community. Does this mean that every article in Journal X is better than any article in Journal Y? Of course it doesn’t, although it probably means that X attracts a better standard of submission and that through this it has some glory to reflect onto your work if you publish in it. The main aim of publishing should always be to communicate interesting and valuable work, but if a secondary aim is for that work to be read and cited and for this activity to contribute towards a favourable research evaluation score, then a more highly-cited journal will always make more sense. It’s a bit like putting your shop in the High Street, or in a Mall.

A step too far …

But that’s really all there is to it, and good work can be found in all sorts of places. While it’s true that very good journals are unlikely to publish very bad work (or at least not knowingly), the measurable quality of a journal does not stand as a proxy for the quality of all the papers that it publishes, and while publishing in Journal X may confer bragging rights or the opportunity to speak patronisingly to a colleague who published in Journal Y, it does not of itself carry any more meaning than that. This is how the UK’s Research Excellence Framework for 2014 puts it in their Research Outputs FAQs –

“How will journal impact factors, rankings or lists, or the perceived standing of publishers be used to inform the assessment of research outputs?

No sub-panel will make any use of journal impact factors, rankings, lists or the perceived standing of publishers in assessing the quality of research outputs. An underpinning principle of the REF is that all types of research and all forms of research outputs across all disciplines shall be assessed on a fair and equal basis.”

In other words, any given piece of work needs to stand on its own merits.

Surely though, it might be objected, we just know that these journals are better than those ones and surely it follows from this that their articles are better. On average that is true, at least if we use the terms “highly-cited” and “better” interchangeably, but if we use the citedness of the journal as a proxy for each of its papers then we assign this average value to both its lowest quality and its highest quality work. It’s a bit like saying that because I’m a New Zealand male in the 45-65 age range then I must be 1.745 metres tall. I’m not, and very few people are, the vast majority are either taller than that or shorter, and often by sizable margins. Exactly the same logic applies to journal titles and if we use them as markers of research quality then the whole business of research assessment is handed over to anonymous peer-reviewers who are, after all, generally only trying to make a fair assessment of whether the work in front of them is a good fit for the journal. If there is a citation measure that counts it will be the number of times the actual paper is cited and that figure may take a number of years to emerge – which is only right and proper because it will reflect the considered verdict of the research community and not a simple yes or no from editors and reviewers. Publishing in Journal X may confer prestige but that is not the same thing as identifying quality and to confuse the two is to fall for the Cart-Before-the-Horse Fallacy. And there you go.

More on ranked lists to come.

Bruce White

eResearch Librarian

*There is no MJRM, I just made that up. Sorry.

Search posts

Categories

Tags

Recent Comments

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- September 2009

- November 2008

Leave a Reply